Hornets Nest Elementary

I have taught several gifted students who read at or above grade level when it comes to literature, but their comprehension of informational text is below standard. They prefer to read novels and love participating in literature circle discussions, but shy away from anything that resembles nonfiction. They insist that textbooks are boring, the words are too hard to understand, and they cannot relate to the information. As I considered all the wonderful ways to teach informational text, I realized I could provide solutions these concerns. In fact, I feel a sense of urgency and obligation to make sure my gifted students are equipped with the most purposeful strategies for learning with informational text. I want them to enjoy the informational text journey, and continue reading for information long into future.

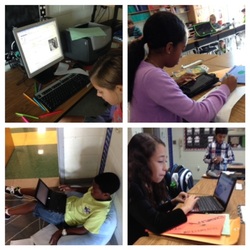

How is the journey and exploration of nonfiction, especially informational text, so different from those childhood storybooks? Why is it so easy for gifted children to listen to a bedtime story, but difficult for these same students to comprehend the vocabulary in a sixth grade science textbook in order to learn about the anatomy of an amphibian? Does technology provide an outlet for the gifted population to understand the academic language of nonfiction? Finally, is it possible to combine traditional reading methods and more innovative strategies, in order to teach gifted students the complexities of informational text? Regardless of the strategies we use for teaching gifted students about informational text, we must have resources and current technology on campus.

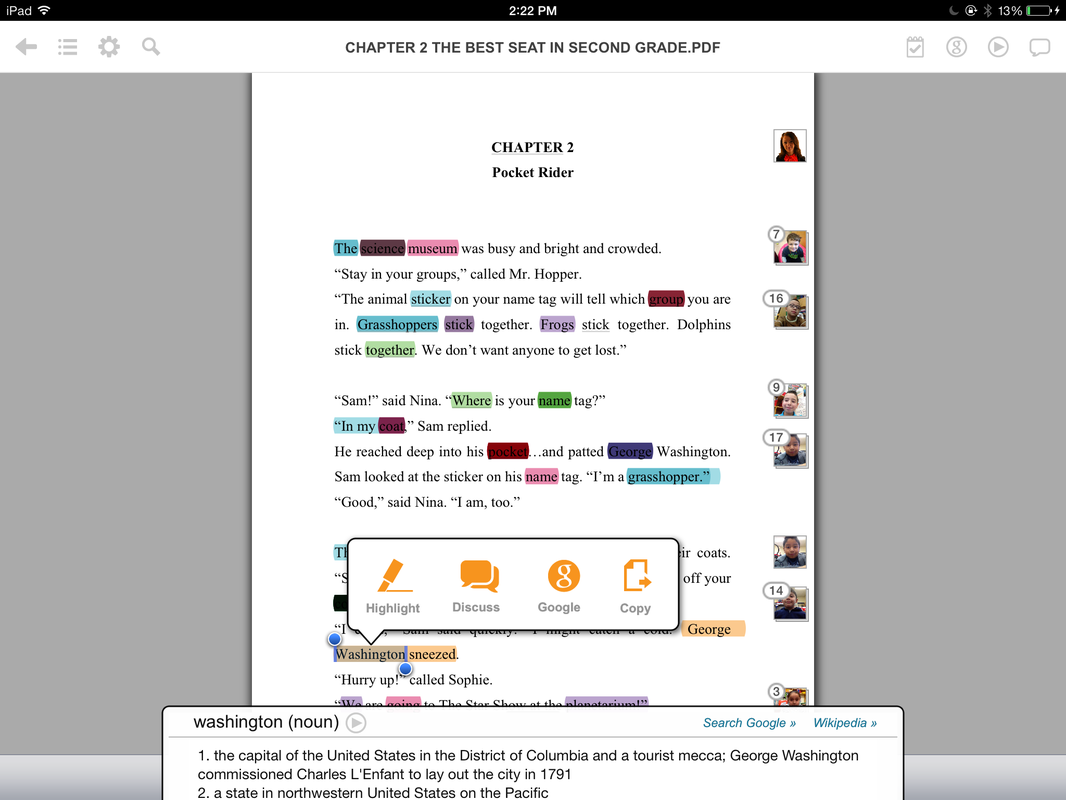

As students move from elementary school to middle school, they are exposed to more informational text, however, they are no more prepared to tackle the difficult, academic vocabulary (Ness, 2011). The strategies used for teaching narrative text does not translate to the material found in traditional textbooks (Ness, 2011), so this leaves students struggling to make connections with the information (Ness, 2011; Shanahan, Fisher, & Frey, 2012). Soalt (2005) suggests the developing units that incorporate fiction and informational texts in order to provide students with a "big picture" for the material. (p. 680) Oftentimes, students have difficulty understanding the academic vocabulary presented in the text, so this hiccup in understanding creates a severe chasm between reading and comprehension (Dalton & Grisham, 2011; Newkirk, 2012; Shanahan, Fisher, & Frey, 2012; Soalt, 2005). Informational texts are also more subject-specific and require greater background knowledge (Mantzicopoulos & Patrick, 2011; Shanahan, Fisher, & Frey, 2012; Soalt, 2005).

The good news is gifted students have a strong preference for “adding to their storehouse of knowledge” (Leal & Moss, 1999, p. 88) so learning new math vocabulary or background knowledge on the start of World War II is a way for them to increase their information bank. Gifted children also appreciate out-of-the ordinary information and more creative aspects of informational texts, such as charts, graphs, illustrations and “mind-boggling details that stimulate the imagination” (Leal & Moss, 1999, p. 97). Learning new information, specifically content vocabulary gives gifted students a chance to transfer their knowledge into other areas of school, in turn increasing their confidence for learning and possibility for reaching their full academic potential (Robinson, 2002). For instance, reading Susan B. Anthony’s biography and learning about the elements of a great newspaper article could inspire one gifted child to write an editorial on women’s rights to the local newspaper.

Remember that initial memory of hearing a story read aloud? At some point the read-alouds might disappear from the every day school schedule, but students need those story-like elements in order to process informational text (Cummins & Stallmeyer-Gerard, 2011; Leal & Moss, 1999; Newkirk, 2005; Mantzicopoulos & Patrick, 2011). Reading an informational text aloud provides gifted students the chance to decipher the overall language of the text (Mantzicopoulos & Patrick, 2011) and gives them a chance to spark their natural curiosity for learning new material (Robinson, 2002). The spark for learning translates into life-long learning and researchers with a love and motivation for new information (Mantzicopoulos & Patrick, 2011). I have a gifted student, Zoe, who reads with an amazing fluency rate, but her informational text comprehension is not where it should be at her age. We recently read Nelson Mandela’s biography, in an attempt to prepare for a Black History Month project. She told me one of her favorite parts of the time we spent reading the book was when I read aloud to the small group. Children, especially gifted students, benefit from “continuous interactions between the reader, the text, and the context” (Leal & Moss, 1999). Zoe could have read every bit of the biography on her own, but I knew she would be more engaged and more likely to comprehend the information if I read aloud during our learning sessions.

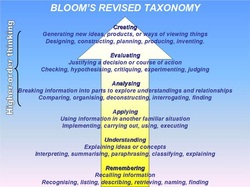

In order to increase background knowledge on an upcoming unit, students could also take a virtual scavenger hunt through various websites and resources. During a recent unit on Penguins, I created an interactive exploration page for gifted second graders. The students traveled from one informational website to another skimming and reading for information to satisfy each component of the scavenger hunt. The students were not looking for terribly in-depth information; they were just gathering knowledge on a particular subject, so they would be prepared for the more complex tasks I had planned. This information exploration provided just enough knowledge to give them the confidence they needed to more forward in becoming a true expert on the topic (Robinson, 2002). Moving forward, the students entered into a series of tasks such as making connections, sequencing, and summarizing. Without the initial background knowledge they gathered on the virtual scavenger hunt, my gifted students may have become more concerned about the process than the actual product.

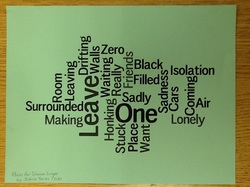

Since we know that students need a working, content-related vocabulary to comprehend complex informational texts (Dalton & Grisham, 2011; Newkirk, 2012; Shanahan, Fisher, & Frey, 2012; Soalt, 2005), it is important to engage gifted learners in creating their own vocabulary banks. One way to incorporate new vocabulary and technology is the use of online word webs, especially the free web application Wordle (www.wordle.net). On Wordle students can create a word cloud with new content-specific vocabulary, giving them the chance to design and adjust the word web as they learn new vocabulary. The word webs can be manipulated to show relationships, such as cause and effect or an underlying theme to the informational text (Dalton & Grisham, 2011). Gathering new words can be a pre-reading activity at the beginning of a new unit in their biology textbook or a culminating project after reading Helen Keller’s biography.

It is important to provide gifted students, especially gifted boys, the choice to be involved in their academic opportunities (Hebert & Pagnani, 2010; Robinson, 2002). Interestingly enough, boys typically choose nonfiction over fiction, while gifted girls will often choose fictional stories (Hebert & Pagnani, 2010). Allowing students to choose their reading material or learning products will give them a sense of motivation and potentially increase their overall engagement in the process (Hebert & Pagnani, 2010; Leal & Moss, 1999; Robinson, 2002; Soalt 2005). For example, I use the R.A.F.T. strategy with many upper elementary gifted students. R.A.F.T., which stands for Role/Audience/Format/Topic (Santa, 1988), is a “writing-to-learn” strategy for improving the understanding of informational texts. Students have the option to choose each of the four elements, as it relates to the topic or subject they are currently studying in class. The process of completing the R.A.F.T. is engaging, multi-disciplinary, and motivating for many gifted students.

Sam, a gifted fifth grader, completed a R.A.F.T. after reading about the events leading up to the signing of the Constitution of the United States of America. He chose the role of a 21st Century American, writing a thank-you letter to James Madison. He mentioned how important it was for Madison to sign the U.S. Constitution, and incorporated informational elements that he had been studying throughout their social studies unit. His writing was very specific and full of excellent, factual details. Typically Sam is apprehensive when it comes to writing his thoughts on paper, but knowing his love of U.S. history, I encouraged him to choose something he was passionate about.Using the R.A.F.T. gave Sam the confidence to proceed with the assignment, while still satisfying the need for processing and incorporating informational text into the task.

Although there are many ways to integrate informational text into the classroom, sometimes the technology and resources are unavailable (Baker, Dreher, Shiplet, Beall, Voelker, Garrett, Schugar, & Finger-Elam, 2011; Jeong, Gaffney, & Choi, 2010; Ness, 2011). In fact, Baker et al. (2011) reports that many classroom libraries contain mostly fiction. However, children chose informational texts twice as often as fiction during their weekly library visits (Ness, 2011), which indicates a growing interest in informational text. The amount of informational text within school assessments and state standardized tests continue to increase every year (Ness, 2011). Providing informational text options within the classroom is important for academic preparation, but more importantly, it is a general life skill (Ness, 2011).

So, how do teachers use informational text in their lessons if the resources are not available? The absence of informational texts presents a complication for encouraging students to dig deeper into content-specific books and current events. As teachers, we must encourage administrators to consider subscriptions to online informational resources, such as Discovery Education (www.discoveryeducation.com) and magazines like Time for Kids. Perhapsfunding for these materials should be included in grade level requests from year to year, or a part of the donations that come from the school community. Regardless of the source, it is evident that securing proper informational text materials is imperative for the success of each student, especially those students who may not have exposure to the materials at outside of the school community.

Parenting Partners

Parents are an integral part of making the connection to understanding informational texts outside of school. For example, encourage parents to read aloud to their children, regardless of the age. Reading aloud to lower elementary students gives them a chance to hear the “sound of informational text” (Cummins & Stallmeyer-Gerard, 2011, p. 400) at an early age, which gives them a chance to make connections to other similar texts. Another superior way to increase comprehension of informational text structure is through general conversation (Cummins & Stallmeyer-Gerard, 2011). Talking about sporting events, new math topics, or the evening news encourages students to fully understand what they are hearing, seeing, and reading. This process will eventually translate to the classroom, and give them a proper segue for comprehending information text at an independent level (Cummins & Stallmeyer-Gerard, 2011; Ness, 2005;Soalt, 2005). Something as simple as working through a family recipe could provide the connections to comprehending informational text at a higher level.

The ability to comprehend informational text is gaining greater importance within the educational community (Cummins & Stallmeyer-Gerard, 2011; Ness, 2011), so the strategies for tackling this genre are equally important. With the proper resources and technology, gifted students will have what they need in order to succeed and excel as informational learners. As educators, we have a duty to ensure that students are given the tools they need to master the many components of informational text, and walk away feeling successful.

For a full list of References, please click here.

Christina Roth is currently the Talent Development/Catalyst Teacher at Oaklawn Language Academy and Hornets Nest Elementary School. She has been an educator for almost 14 years, with experience in both elementary and middle school. She received her master's from Winthrop University in Middle Level Education, followed by her National Board Certification as a Middle Childhood Generalist. As a passionate life-long learner she went on to get her AIG Certification from UNCC and recently finished her ESL Certification through the CMS cohort experience. During her spare time she is an avid CrossFitter and works as a contracted writer for the CrossFit Games website, runs a small online, gluten-free bakery business, and loves to travel with family and friends.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed